Loi renseignement : « Des dizaines de milliers de personnes vont être suspectées à tort »

En savoir plus sur http://www.lemonde.fr/pixels/article/2015/05/06/loi-renseignement-des-dizaines-de-milliers-de-personnes-vont-etre-suspectees-a-tort_4628392_4408996.html

Jun 11

Loi renseignement : « Des dizaines de milliers de personnes vont être suspectées à tort » Entretien de C. Castelluccia et D. Le Métayer dans Le Monde 2015/05/06.

Oct 10

Vincent Roca received FIEEC 2014 Applied Research Award for Industrial Transfer of his Research to French Start-up Expway

Vincent Roca, researcher in Privatics team, received FIEEC 2014 applied research award for industrial transfer of his research to French start-up Expway, specialized in broadcasting in IP networks and mobile services like Direct Television or Datacasting.

For more information (in French): http://www.inria.fr/centre/grenoble/actualites/vincent-roca-recompense-pour-ses-activites-de-transfert-industriel

Feb 07

Facebook, n’en fais pas une affaire de données personnelles ! Article de C. Castelluccia et A. Chaabane dans InaGlobal

Claude Castelluccia et Abdelberi Chaabane, membres de l’équipe Privatics, parlent des problèmes de vie privée dans les réseaux sociaux dans un article publié dans InaGlobal.

C’est à lire ici : http://www.inaglobal.fr/numerique/article/facebook-nen-fais-pas-une-affaire-de-donnees-personnelles

Sep 05

La vie privée, un obstacle à l’économie numérique ? Tribune de C. Castelluccia et D. Le Métayer dans Le Monde

A l’heure où de plus en plus d’affaires montrent que des citoyens sont espionnés, traqués, profilés par de grandes sociétés aussi bien que par des Etats, les attitudes de certains commentateurs vont de la résignation (“C’est le prix à payer pour le développement de nouveaux services”) à l’approbation moralisatrice (le fameux “Si vous ne voulez pas que les autres sachent ce que vous faites, le plus simple est de ne pas le faire”, d’Eric Schmidt, PDG de Google) ou à l’attaque frontale (l’inconséquent “La Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés est un ennemi de la nation” de Gilles Babinet, responsable des enjeux du numérique pour la France auprès de la Commission européenne)….

La suite…

sur notre site: Lemonde30Aout

ou sur le site Du Monde: http://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2013/08/25/la-vie-privee-un-obstacle-a-l-economie-numerique_3466139_3234.html

Jul 02

Paris Metro Tracks and Trackers: Why is the RATP App leaking my private data? (Continued…)

The PRIVATICS Inria team – July 2nd, 2013 – https://team.inria.fr/privatics/

(this blog has been modified on July 5th, 2013 upon request of FaberNovel)

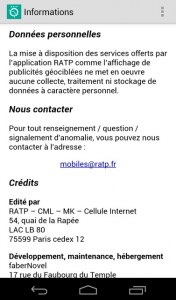

The RATP Android App

This post is follow-up of our previous post about private data leakage by the RATP’s iOS App. To make our study complete, we also analyzed the RATP Android App (version 2.8), once again developed by FaberNovel as mentioned in the screenshot below. We also see the same privacy policy as that of the iOS version: “The services provided by the RATP application, like displaying geo-targeted ads, do not involve any collection, processing or storage of personal data” (translated).

So we wanted to know if this Android version differs from the iOS version with respect to personal information collection. And here are our findings…

Below is what we captured being sent to the network in cleartext by the RATP’s Android App (you can see that our curiosity didn’t go into vain 😉 ):

{"user_position":"45.2115529;5.8037135", "ugender":"", "test":"", "uage":"0", "imei":"56b4153b8bd2f6fd242d84b3f63e287", "napp":null, "uemail":"", "pid":"4ed37f3f20b4f", "alid":"114", "uzip":"", "osversion":"3.0.31-g396c4df-dirty", "lang":"en_En", "sal":"", "network":"na", "adpos":null, "time":"Tue Jun 04 12:05:39 UTC+02:00 2013", "sdkversion":"3.2", "ua":"Mozilla\/5.0 (Linux; U; Android 4.1.1; fr-fr; Full AOSP on Maguro Build\/JRO03R) AppleWebKit\/534.30 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version\/4.0 Mobile Safari\/534.30","udob":"",

"carrier":"Orange F","longitude":"0.0","latitude":"0.0","freespace":null,"unick":null}]

Above data contains some very sensitive info about the user, in particular:

- the exact location: Scary… hmmm?

- the MD5 hash of device’s IMEI: researchers are working on quantifying out how easy it is to get back the IMEI from its hash given some info about the device. For example, if the smartphone manufacturer and model are known, it only takes ~1 second to get back the IMEI of the device! Said differently, one could send the IMEI directly, it wouldn’t change so much the security level achieved in front of a motivated attacker;

- the SIM card’s carrier/operator name.

This is certainly not acceptable in any case that the App is sending this data in cleartext (no matter to whom or for what matter the info is being sent!). To App developers: for God’s sake, please, don’t make easier the life of a user’s spy or anyone for that matter who can intercept the traffic (ISPs, WiFi AP Owners, Governments etc.). We don’t see any point not to use secure connections!

Now the next question is: Where is this info sent? The answer is: to the 88.190.216.131 IP address. We now need to know which entity/organization this IP address belongs to, for instance to infer the reason why the info might be collected… Whois and other web services (like infosniper, DShield) reveal so-par-onl-vip01.sofialys.net as the hostname of the machine. Second levels domain sofialys points to sofialys as the company this machine belongs to. And finally, the icon almost confirms this as it’s the same on sofialys webpage [Courtesy to Vincent Maugé for his help in IP address analysis; updated July 4]!

It is even more disturbing that RATP still keeps continuing these bad practices whereas it has already been highlighted in the past (later, our google search revealed that it’s already known). This is not acceptable.

Then, in order to know if A&A libraries are being used by the App, we decompiled the App’s dex file executed by Dalvik Virtual Machine. We found two third-party packages: Adbox (with package name com.adbox) and HockeyApp (with package name net.hockeyapp). See screenshot listing class descriptors. Adbox is clearly a company that could be interested by these private data.

Also, to our surprise, RATP’s Android App (version 2.8) requires permissions far more than it requires. Why would it need to access the user’s contacts? Here is the list:

com.fabernovel.ratp.permission.C2D_MESSAGE;

com.google.android.c2dm.permission.RECEIVE;

android.permission.READ_PHONE_STATE;

android.permission.VIBRATE;

android.permission.INTERNET;

android.permission.ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION;

android.permission.ACCESS_COARSE_LOCATION;

android.permission.READ_CONTACTS;

android.permission.ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE;

android.permission.READ_CALL_LOG

A final comment: the RATP App asks for permission to access the user exact position and the user has no other choice than agreeing in order to install and use the App. This is acceptable for an application meant to facilitate the use of public transportation. However, even if the user grants this permission to the App, does it imply that the user also accepts this information be sent to a remote, unknown server, with no information of who will store and use this data, and to what purposes? Certainly not. The Android permission system cannot be interpreted as an informed end-user agreement for the collection and use of personal data by third-parties.

Back to the RATP iOS App: does it leak something else?

Let’s come back to the iOS world. Did we miss anything in Part 1 of this blog? Did the iOS App leak more private information than previously mentionned? The answer is Yes! RATP’s iOS App also sends the same info (see below) as its Android App to the ip address 88.190.216.131 in cleartext. The machine corresponding to this ip address belongs to sofialys. The Adbox library from sofialys is included in both Android and iOS versions of RATP App (See screenshot listing headers from Adbox library in RATP’s iPhone App).

"UTFStringOfDataSent": "{\"uage\":\"\",\"confirm\":\"1\",\"imei\":\"9c7a916a1703745ded05debc8c3e97bedbc0bcdd\" ,\"osversion\":\"iPhone 6.1.2\", \"odin\":\"1b84e4efaf650cb9a264a2ff23ca7a67b9bd72f6\" ,\"umail\":\"\", \"carrier\":\"\", \"user_position\":\"45.218156;5.807636\", \"long\":\"\", \"ua\":\"Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 6_1_2 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/536.26 (KHTML, like Gecko) Mobile/10B146\", \"footprint\":{\"v1\":{\"i\":\"3739335834508445\", \"b\":\"c5kkekILx11ghUfu3Ht43bUZWcHHBNbR09AO4it+ wtPPCBJagCIo7tgBdMlq6T244EwHnKRzeh1ybrMhKy2SztEU5tD5u5Q7HAis R57BYIun9aQdp0NsXwp7BXhohS92daScYcMDALqK QhYKZDriEjqWwtjvR9MrIKfE52EwNcA9CJJkUIT9q7sXkqkvaloOM7tMrNdMiIQYyH0tdNJ + ax7Ujau/IQ4pPasSXk/m6BIFsAFhjFOng0NuSwtL7e7r95s8wQhWy + EvJUChPIvIRXZYldCbjfdkrkvNgHZcH59Fj0dBz9Ugbyoj4a/Z60SlU + EatvNswORMQqdE8djVJmXkGCmwoheU10uQatr4pqA =\"}}, \"ugender\":\"\", \"os\":\"iPhone \", \"adid\":\"496EA6D1-5753-40B2-A5C9-5841738374A2\", \"uphone\":\"\", \"sdkversion\":\"5.0.3\", \"test\":\"\", \"lat\":\"\", \"udob\":\"\", \"pid\":\"4ed37f3f20b4f\", \"lang\":\"fr_FR\", \"network\":\"wifi\", \"time\":\"2013-05-30 15:45:04\", \"alid\":\"186\", \"sal\":\"\", \"uzip\":\"\"}",

Here, the IMEI is replaced by the UDID (Unique Device Identifier) of the iPhone. Otherwise the precise geolocation of the user is also captured and sent, and all of this happens in addition to the private data sent to Adgoji as we mentioned in our first blog post.

To Conclude…

The RATP App, both the iOS and Android versions, is a good illustration of bad privacy practices of some companies, in particular A&A companies:

- many kinds of private data are collected and sent, and in this example, even if the “legal terms” of the RATP App claims the contrary;

- A&A companies have found ways and started using techniques to bypass the restrictions imposed by Apple. The fact that the user can reset the Advertising ID as often as he wants is annoying from a tracking point of view (that’s the goal), and as a result, certain tracking companies started using permanent (or at least long-term) identifiers to track the user;

- the Android permission system does not help so much in controlling what information is captured and sent: it’s a coarse grain system that often cannot tell the difference between what is legitimate and not. And we have the feeling these authorizations are interpreted by trackers as an implicit authorization of the end-user to do whatever is technically possible;

- the Apple privacy dashboard added in iOS6 does not help so much either:

- items are missing (for example, Device Name, Internet usage) and techniques exist to bypass some of the limitations imposed (for example WRT the Advertising ID restrictions). Fortunately, the access to the MAC address seems to be banned from the new iOS7 version, but what about the rest?

- A&A libraries included by the App developer have access to the same set of user’s private data as the App itself. However, a user accepting that an App has access to his or her Contacts doesn’t necessarily indicate consent for this data to be shared with third parties. Whether and where personal information is sent is not under the user control via the privacy dashboard;

- is an authorization system that does not consider any behavioral analysis sufficient? For instance, accessing the device location upon App installation to enable a per-country personalization is not comparable to accessing the location every five minutes. That’s a fundamental limit of the privacy dashboard system (and the Android authorization system too);

- all this happens without the user knowledge…

- …and probably without the App developer knowledge. The A&A libraries are often included by App developers without knowing their exact behavior. And if App developers get money by including these libraries in their App without being afraid of privacy-enforcement authorities (for example, if there is little or no risk of legal action), they probably won’t care too much whether these added libraries respect the user’s privacy or not.

You might also be interested in Paris Metro Tracks and Trackers: Why is the RATP App leaking my private data?

Contacts : Jagdish Achara, James Lefruit, Vincent Roca, Claude Castelluccia

The PRIVATICS Inria team – July 2nd, 2013 – https://team.inria.fr/privatics/

———————————————————————————————-

The answer of RATP (added on July 5th, 2013):

RATP wishes to reply in light of the publication of our blog with the following items of additional information:

Data exchanges with the Adgoji server

– SDK Sofialys (the adserving company for our online advertising sales service) sends information to the Adgoji server, the Fly Targeting system that provides contextual information about the public based on the applications installed on the terminal. Information recovered by SDK is processed for analysis, but does not make it possible under any circumstances to identify the data user.

– No data collected by Adgoji concerning users of the RATP app have been used. The Fly Targeting module was under study in Sofialys, which mistakenly implemented it in its SDK in “production” phases. We are currently removing it from SDK.

Furthermore, we confirm that no personal data are used. In accordance with Apple directives, the UDID stopped being used last year. As for the IMEI: although the ID is already hashed, we are requesting a higher level of encryption for the next revision of SDK.

Jul 02

Paris Metro Tracks and Trackers: Why is the RATP App leaking my private data?

The PRIVATICS Inria team – July 2nd, 2013 – https://team.inria.fr/privatics/

(this blog has been modified on July 5th, 2013 upon request of FaberNovel)

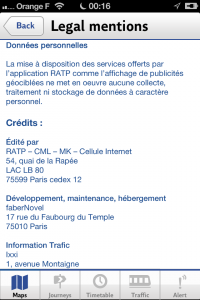

The RATP iOS App

The RATP is the French public company that is managing the Paris subway (metro). It provides a dedicated and very useful smartphone App. In particular, privacy policy of RATP’s iOS App (version 5.4.1) claims: “The services provided by the RATP application, like displaying geo-targeted ads, does not involve any collection, processing or storage of personal data” (translated from their privacy policy, in French). Below is the screenshot of RATP’s In-App privacy policy (in French). It also says that this App is, in fact, developed and maintained by FaberNovel.

Now, having read above the privacy policy of the App, would you believe the fact that MAC Address of your iPhone’s WiFi chip, your iPhone’s name, and the list of processes running on it (which potentially reveals a subset of Apps installed on the smartphone) among other things, are being sent over the network to a remote third-party by RATP App? Well, if you don’t believe it; here you go. Below are two instances of data we captured on our iPhone while being sent over the network by the RATP App. One good news, though: this data is sent through SSL, not in clear, which avoids eavesdropping.

UTF8StringOfDataSentThroughSSL = {"p":["kernel_task", "launchd", "UserEventAgent", "sbsettingsd", "wifid", "powerd", "lockdownd", "mediaserverd", "mDNSResponder", "locationd", "imagent", "iaptransportd", "fseventsd", "fairplayd.N94", "configd", "kbd", "CommCenter", "BTServer", "notifyd", "aggregated", "networkd", "itunesstored", "apsd", "MyWiCore", "distnoted", "tccd", "filecoordination", "installd", "absinthed", "timed", "geod", "networkd_privile", "lsd","xpcd", "accountsd", "notification_pro", "coresymbolicatio", "assetsd", "AppleIDAuthAgent", "dataaccessd", "SCHelper", "backboardd", "ptpd", "syslogd", "dbstorage", "SpringBoard", "Facebook", "iFile_", "Messenger", "MobilePhone", "MobileVOIP", "MobileSafari", "webbookmarksd", "eapolclient", "mobile_installat", "AppStore", "syncdefaultsd", "sociald", "sandboxd", "RATP", "pasteboardd"], "additional":{"device_language":"en", "country_code":"FR" ,"adgoji_sdk_version":"v2.0.2", "device_system_name":"iPhone OS", "device_jailbroken":true, "bundle_version":"5.4.1", "vendorid":"CECC8023-98A2-4005-A1FB-96E3C3DA1E79", "allows_voip":false, "device_model":"iPhone", "macaddress":"60facda10c20", "asid":"496EA6D1-5753-40B2-A5C9-5841738374A2", "bundle_identifier":"com.ratp.ratp", "system_os_version_name":"iPhone OS", "device_name":"Jagdish's iPhone", "bundle_executable":"RATP", "device_localized_model":"iPhone", "openudid":"9c7a916a1703745ded05debc8c3e97bedbc0bcdd"}, "e":{"782EAF8A-FF82-48EF-B619-211A5CF1F654": [{"n":"start", "t":1369926018, "nonce":"IEx9HAzG" }]}}

UTF8StringOfDataSentThroughSSL = {"s":["fb210831918949520", "fb108880882526064", "evernote", "fbauth2", "fbauth", "fb", "fblogin", "fspot-image", "fb308918024569", "fspot", "fsq+pjq45qactoijhuqf5l21d5tyur0zosvwmfadyw0pvd4b434e+authorize", "fsq+pjq45qactoijhuqf5l21d5tyur0zosvwmfadyw0pvd4b434e+reply", "fsq+pjq45qactoijhuqf5l21d5tyur0zosvwmfadyw0pvd4b434e+post", "foursquareplugins", "foursquare", "fb86734274142", "fb124024574287414", "instagram", "fsq+kylm3gjcbtswk4rambrt4uyzq1dqcoc0n2hyjgcvbcbe54rj+post", "fb-messenger", "fb237759909591655", "RunKeeperPro", "fb62572192129", "fb76446685859", "fb142349171124", "soundcloud", "fb19507961798", "x-soundcloud", "fb110144382383802", "mailto", "spotify", "fb134519659678", "fb174829003346", "fb109306535771", "tjc459035295", "twitter", "com.twitter.twitter-iphone", "com.twitter.twitter-iphone+1.0.0", "tweetie", "com.atebits.Tweetie2", "com.atebits.Tweetie2+2.0.0", "com.atebits.Tweetie2+2.1.0", "com.atebits.Tweetie2+2.1.1", "com.atebits.Tweetie2+3.0.0", "FTP", "PPClient", "fb184136951108"]}

Fortunately, it’s not trivial to detect all the Apps installed on the iPhone because 1) iOS doesn’t provide an API to do so, and 2) due to sandbox restrictions, an App can’t peak into other system activities. However, since this is a highly valuable information to infer the user’s interests, techniques exist to identify some of them. Here are some techniques:

- listing the currently running processes using sysctl (We decrypted and opened the RATP binary in a hexeditor and searched for sysctl; See screenshot. It confirms the use of sysctl function in the RATP App).

- detecting if a custom url can be handled or not (one can use canOpenURL function of UIApplication class. See more about URLSchemes.). If the url is handled, it confirm the presence of a particular App. You get the answer, but of course this technique requires you actively search for an App by yourself.

Now, the natural question arising in one’s mind would be: Why does the RATP App collect this info whereas they deny to do so in their In-App privacy policy? Well, to your surprise (or not to your surprise if you already aware of these Analytics and Advertising tracking companies), this data is sent to a server named sdk1.adgoji.com (IP Address:Port Number 175.135.20.107:47873) owned by Adgoji, a mobile audience targeting company. Does this company share this data back to RATP? We cannot say. In any case, it’s unclear how Adgoji treats the data and to whom the data is shared with. The questions remain… and only the parties involved can answer what terms and conditions they agreed upon.

Here is a screenshot where decrypted RATP app binary is opened in IDA Pro; you can see some methods inside AppDetectionController and AdGoJiModel class. The internals of the RATP App reveal that it uses the Adgoji library, which, in turn, does the job of collecting and sending the info to their server [Here are the name of header files generated by running class-dump-z on the decrypted binary revealing the classes from Adgoji company starting with prefix Adgoji].

To summarize, Adgoji tries to detect the Apps present on the phone to target the users based on their interests (e.g. if a user is a gamer or news reader or runner or blogger or radio listener etc.). Adgoji also collects the MAC Address, a permanent unique identifier attached to the device, to keep track of the device. They collect the device name as well, probably to infer the gender/country of the user.

What about Apple?

Well, Apple gives users a perception that they can control what private information is accessible to Apps in iOS 6. That’s true in case of Location, Contacts, Calendar, Reminders, Photos, and even your Twitter or Facebook account but Apps can still access other kinds of private data (for example, the MAC Address, Device Name, List of processes currently running etc.) without users’ knowledge. To avoid device tracking, Apple has deprecated the use of the permanent UDID and replaced it by a dedicated “AdvertisingID” that a user can reset at any time. This is certainly a good step to give control back to the user; by resetting this advertising identifier, trackers should not be able to link what you’ve done in the past with what you’ll be doing from that point onwards. But apparently, the reality is totally different: it only gives an illusion to the user that he is able to opt-out from device tracking because many tracking libraries are using other stable identifiers to do that:

- Apps can access MAC address (again through sysctl function in libC dylib) to get a unique identifier permanently tied to a device which cannot be changed. Fortunately, the access to the MAC address seems to be banned from the new iOS7 version;

- Apps can use UIPasteboard to share data (e.g. a unique identifier) between Apps on a particular device. For example, Flurry analytics library, also included in this App binary, is doing it! Flurry creates a new pasteboard item with name com.flurry.pasteboard of pasteboard type com.flurry.UID and stores a unique identifier whose hexadecimal representation looks like this 49443337 38383436 44452d32 3138302d 34414231 2d423536 432d3936 38363839 36443736 35333532 30443544 3338. A lot of other analytic companies are using the OpenUDID (which is again based on the use of UIPasteboard to share data between each other). Resetting the advertising ID will not impact this OpenUDID;

- Apps can use the device name as an identifier, even if it’s far from being a unique identifier. Who cares to change it periodically? Even if it’s not unique, this is in practice a relatively stable identifier;

- Or, simply, Apps can store the advertising identifier in some permanent place (e.g. persistent storage on the file system), and later, if this ID has been reset by the user, they can link it with the new advertising identifier. That’s so trivial to do…

We see there are several effective techniques to identify a terminal in the long term, and Apple cannot ignore this trend. Apple needs to take some rigorous steps in regulating these practices.

Also, we don’t understand why Apple is not giving control to the user to let him choose if an App can access the device name or not (we’ve seen that this is an information commonly collected). Earlier this year, we’ve developed an extension to the iOS6 privacy dashboard to demonstrate it’s feasibility and usefulness. Our extension to the privacy dashboard lets users choose if an App can access the device name (that often contains the real name of the iPhone owner) and if it can access the Internet (See our privacy extension package). It’s not sufficient, for sure, but it’s required.

You might also be interested in Paris Metro Tracks and Trackers: Why is RATP App leaking my private data? (Continued…)

Contact: Jagdish Achara, Vincent Roca, Claude Castelluccia

The PRIVATICS Inria team – July 2nd, 2013 – https://team.inria.fr/privatics/

———————————————————————————————-

The answer of RATP (added on July 5th, 2013):

RATP wishes to reply in light of the publication of our blog with the following items of additional information:

Data exchanges with the Adgoji server

– SDK Sofialys (the adserving company for our online advertising sales service) sends information to the Adgoji server, the Fly Targeting system that provides contextual information about the public based on the applications installed on the terminal. Information recovered by SDK is processed for analysis, but does not make it possible under any circumstances to identify the data user.

– No data collected by Adgoji concerning users of the RATP app have been used. The Fly Targeting module was under study in Sofialys, which mistakenly implemented it in its SDK in “production” phases. We are currently removing it from SDK.

Furthermore, we confirm that no personal data are used. In accordance with Apple directives, the UDID stopped being used last year. As for the IMEI: although the ID is already hashed, we are requesting a higher level of encryption for the next revision of SDK.

Jun 21

Comment protéger sa vie privée sur Internet

De récentes révélations ont mis en évidence des programmes de surveillance à grande échelle. Nous présentons ici un guide permettant aux utilisateurs soucieux de leur vie privée de se prémunir des menaces qui pèsent sur leurs informations personnelles. Ce guide se présente sous la forme d’une liste d’outils logiciels ou services qui permettent d’empêcher ou de limiter la collecte d’information personnelles lors de leurs activités dans le monde numérique.

Des outils et des solutions pour protéger notre vie privée

La liste suivante contient un ensemble d’outils qui permettent de protéger notre vie privée. Une partie de ces outils reposent sur l’utilisation d’outils cryptographique, qui permettent des communications sécurisées en assurant en particulier la confidentialité des messages échangées. D’autres outils bloquent la collecte de données personnelles ou reposent tout simplement sur des services qui ont fait le choix de ne pas collecter d’informations sur leurs utilisateurs.

Moteur de recherche

La plupart des moteurs de recherche collectent des informations sur leurs utilisateurs (mots clefs, adresse IP). Il existe des moteurs de recherche qui ne collectent pas ces informations :

Navigateur Web

Lorsque vous naviguez le web, les pages que vous affichez sont enregistrés par les sites que vous visitez, mais aussi par des entités tierces. Ces entités tierces tracent les utilisateurs afin de créer des profiles qui seront utilisés à des fin marketing. Ce traçage est rendu possible par des mouchards embarqués de manière invisible dans les pages Web. Il est possible de se prémunir contre ce profilage en utilisant des modules bloquant ces mouchards.

- AdBlock pour Chrome et Adblock Plus pour Firefox

- FlashBlock pour Chrome ou Firefox

- Disconnect pour Chrome et Firefox

Il est possible de sécuriser l’utilisation du Web de manière à garantir la confidentialité de vos communications (pages affichées, mots de passe) mais aussi à s’assurer que le site que vous visitez est bien celui qu’il prétend être. Si beaucoup de site Web supportent la sécurisation des connexions, essentielle pour votre sécurité et votre vie privée, un certain nombre d’acteurs ne l’activent pas par défaut. Pour activer cette sécurisation partout où elle est possible, vous pouvez utiliser la solution suivante :

- HTTPS Everywhere pour Firefox et Chrome

Pour mesurer l’ampleur du traçage sur Internet, vous pouvez utiliser le module Collusion (pour Chrome ou Firefox) qui permet de visualiser en temps réel les entités qui tracent vos activités sur le Web. Si la nationalité des serveurs Web a une importance pour vous, il y a de module FlagFox qui affiche sous la forme d’un drapeau la localisation du site Web affiché.

E-mails

Que ce soit lorsqu’ils sont transmis sur Internet ou lorsqu’ils sont stockés dans nos boite mail, nos e-mails sont directement lisibles par toute personne capable d’intercepter les communications ou d’accéder aux serveurs hébergeant notre boite au lettre électronique. Pourtant il existe un moyen simple de garantir la confidentialité de notre correspondance : la cryptographie. Voici un ensemble de logiciels permettant de protéger vos e-mails grâce à la cryptographie.

- Thunderbird et le module Enigmail

- Gnu Privacy Guard et un des nombreux clients mails compatibles

- Encrypted Communication un module Firefox pour chiffrer simplement ses e-mails

Téléphonie et SMS

Les communications téléphoniques comme les SMS peuvent être interceptés et collectés. Il est possible de protéger la confidentialité de nos conversations téléphoniques et de nos messages en utilisant des applications mobiles utilisant des outils cryptographiques.

Pour les téléphones Android :

- RedPhone pour sécuriser les conversations téléphoniques sur Android

- Gibberbot et TextSecure pour sécuriser les échanges de SMS et de MMS

- Signal pour sécuriser conversations téléphoniques et SMS sur iOS

VoIP et messagerie instantanée

Que ce soit pour communiquer avec nos proches ou nos collègues, nous utilisons de plus en plus les systèmes de voix sur IP et de messagerie instantanée. A l’image de nos e-mails, ces communications peuvent également être interceptées. Il existe des alternatives aux traditionnels logiciels de messagerie instantanée qui peuvent garantir la confidentialité des messages échangés grâce aux outils cryptographiques qu’ils intègrent.

- Pidgin avec le module OTR (Windows, Linux, MacOS)

- Cryptocat pour Chrome et Firefox

- Jitsi avec le support de OTR

Cartes et géolocalisation

A l’image des moteurs de recherche et des pages Web, les services de cartographie en ligne collectent des informations sur leurs utilisateur. Ici encore, il existe des services alternatifs qui respectent la vie privée de leurs utilisateurs.

Anonymat sur Internet

Sur internet, les ordinateurs sont identifiés par un identifiant appelé adresse IP. Cette adresse est utilisée pour tracer les utilisateurs et peut éventuellement permettre de remonter à leur identité réel. Elle est d’ailleurs enregistrée par la plupart des services auxquels nos accédons. Pour protéger notre vie privée, il peut ainsi être utile de cacher sa véritable adresse IP avec les outils suivants :

- Tor le réseau d’anonymisation décentralisé

- Tor Browser Bundle pour une utilisation facile de Tor

- Orbot pour utiliser Tor sur son smartphone

Warning!

L’équipe Privatics n’a pas effectué d’analyse détaillée de ces outils, et ne peut donc garantir leur fiabilité.Pour toute remarque suggestion d’outils, contactez mathieu.cunche@inria.fr.

L’équipe Privatics

Apr 23

PhD positions opening at INRIA-Privatics

We have three PhD positions available for highly motivated students interested in privacy. For more information, see the job section : jobs.

Apr 18

First results of the Mobilitics project

Last week, Inria and CNIL (french data protection agency) have published the first results of the Mobilitics project. This collaborative project between CNIL and Inria Privatics team aims to investigate privacy concerns for smartphone users. Those results shows that mobile application are accessing private information more than necessary.

- CNIL’s website (fr): Voyage au cœur des smartphones et des applications mobiles avec la CNIL et Inria

- ERCIM News: Mobilitics: Analyzing Privacy Leaks in Smartphones

Mar 12

Seminar on Software Define Radio, Security and Hacking

Seminar on Software Define Radio, security and hacking at CITI Lab (INSA-Lyon) – 13/03/2013, 14h – TD E. [link]

- Relay Attacks on Passive Keyless Entry and Start Systems in Modern Cars (Aurélien Francillon – EURECOM)

- On security aspects of ADS-B and other “flying” technology (Andrei Costin – EURECOM)